- Home

- Robin LaFevers

Dark Triumph (His Fair Assassin #2) Page 16

Dark Triumph (His Fair Assassin #2) Read online

Page 16

I decide that it is a very good thing I did not tell him that Alyse died trying to help me.

Chapter Twenty-One

IN THE MORNING, WE MAKE ready to leave. Anton and Jacques are desperate to saddle up the dead Frenchmen’s horses, grab their new weapons, and follow us to Rennes, but we refuse their offer. There are at least twelve more leagues between here and Rennes, all of them crawling with d’Albret’s scouts. We will need the gods’ own luck to get there. Which means it is too dangerous for them to travel with us. “Better to meet us in Rennes in a fortnight,” Beast tells them.

So they content themselves with the plan they cooked up over breakfast. Guion, Anton, and Jacques saddle up the French soldiers’ horses and hoist the dead men across the animals’ backs. They take a tabard Yannic stripped from a d’Albret scout and tie it around one of the dead soldier’s arms. “Maybe that will prod the French to tangle with d’Albret’s men and buy you a little time,” Guion says.

It is a pleasant thought, but in my experience, the gods are not nearly that accommodating.

Then Guion and the two boys lead their grisly retinue south, while Beast, Yannic, and I head north. Our path to Rennes will be like trying to thread a needle, weaving our way through d’Albret’s men to the west, and Châteaubriant to the east with all its ties to the Dinan family and therefore to d’Albret. Not to mention the added spice of French sorties scattered throughout. But we have no choice. We must keep moving, especially if we do not want to risk d’Albret’s stumbling upon this innocent family.

Well, perhaps not so innocent now, after their encounter with the French.

I feel as if the huntsman’s snare is closing in around us, and it has me fair twitching in my saddle. Since I do not wish to spook my horse, I force myself to stillness, an art I have mastered during my long years with d’Albret.

I glance over at Beast. He is still pale, and it seems as if he does not sit as tall in the saddle as he once did. No matter how strong a man he is, he is only human. Or at least, mostly human. It is a wonder he has made it this long, and I can only hope his strength holds until we reach Rennes. Guion told us of a small abbey run by the brothers of Saint Cissonius where we can take shelter for the night.

Unless d’Albret has thought to post guards at all such places.

Hopefully they will have medical supplies as well, for my own stores of healing herbs are running dangerously low. And while Beast’s fever has gotten no worse, neither has it gotten any better. For once, he is being smart and not wasting his dwindling energy. Or at least, not at the moment. Who knows what he will do if we come across some lost goat or wandering child?

I came back for her. The memory of his words still echoes in my head. It makes no sense that five simple words should shift everything so sharply, but they do. It is as if I have woken up in a world as different from yesterday as spring is from winter. It is the difference between a world with hope and one without. I wish to crawl back into my younger self and hand her this knowledge, this small spark of light, and see how it would shift her perceptions of the darkness all around her. Or would it have been more cruel, that glimmer of hope causing her to look for a rescue that never came?

The farther we get from Nantes, the more I am plagued by doubts. While this taste of freedom is as sweet as I dreamed it would be, I cannot help but wonder about the cost. For so long, I was convinced it was my destiny to kill d’Albret. As relieved as I am to be gone from him, I fear I have shirked my fated duty.

But there was no other choice, I remind myself. To have ridden boldly back into his arms after drugging the entire garrison and freeing Beast would only have ensured my slow and painful death.

I also cannot help but worry about the convent and my role there. It was the one place I felt safe from d’Albret, hundreds of leagues away on an island inhabited by assassins. But I have gone against their teachings, their rules, defied Mortain’s will and replaced it with my own. If they cast me out, what then?

Just before noon, the goat track we have been following opens up onto a small meadow. On the far side of the meadow lies the main road, and on the other side of that is the forest. It will be slower going, but d’Albret’s soldiers cannot scour every inch of forest between here and Rennes. With luck, we can avoid being seen.

As we draw closer to the road, I hear the sound of an approaching party. I pause to listen for the distant hoofbeats. More than a few. And they are riding hard. No merchant party, then, nor casual travelers.

The timing could not be worse. I glance behind us, but we have crossed over half the meadow and the shelter of the trees is too far away.

“We must get across the road. Quickly!” I order the others.

The whiff of danger has stirred Beast from his dozing and he spurs his horse forward to the road and the thick screen of trees and low branches on the other side of it. Yannic bounces along behind him like a sack of the miller’s grain, and I bring up the rear, nipping at their heels, urging them to move faster.

We are in luck, for there is a sharp bend in the road, and while the jingle of harnesses and the rattle of weapons grows louder, the party is still out of sight. Which means they cannot see us either. We hit the road at a full gallop and cross it in a few swift strides. Beast reaches the cover of the trees first, then Yannic. Just as my horse leaves the road, a shout goes up from behind. We’ve been spotted.

“Faster!” I shout to the others, but the forest is a tangle of fallen limbs and gnarled roots, forcing us to slow down. Beast falls back to ride beside me. “Return to the road and keep riding. Yannic and I will lead them away.”

“You’re daft!” I shout, ducking a low-hanging branch. “I’ll not leave a wounded man and a cripple to stand alone against so many.”

“Now you’re being daft. Did you see how many there were?”

“Twenty. Maybe more. Here!” We have reached a small clearing with a ring of tall, jagged ancient stones, some of them high and wide enough to hide us from sight. At least until we are ready to make our stand.

Beast’s mouth is set in grim lines as he nods Yannic toward one of the stones. His jaw is clenched—at first I think he is in pain, and then I realize he is furious. “Go!” He puts the full force of command in his low, urgent voice. “I’ll hold them off.”

I look at him in disbelief. “Your fever has eaten your brain if you think I’ll leave now.”

He leans out of his saddle as if to grab me, then stops as his ribs bite him. “This is no fight.”

“I know.” I steer my horse toward one of the stones. The sword is not my favorite weapon, but its longer reach will be of greater value here. Once I take out a few with my throwing knives—

“No!” Beast makes a grab for my reins, but he misses and nearly falls off his horse. “I will not stand by and watch you struck down before me.” His eyes burn—with anger, I think, until I see that he is also afraid. Afraid for me.

His concern inflames my own temper, for I do not deserve such consideration, and certainly not from him. I will not abandon Alyse’s brother like I abandoned her. “And I will not stand idly by and watch you die a second time,” I tell him.

Then d’Albret’s men are hard upon us. Resigned, Beast draws the sword from his back with his right hand while his left closes around the handle of the ax. “I will not let them take you alive.”

Of all the things he could have said, that is the one thing that comforts me the most. “Nor I you,” I say around a strange lump that has formed in my throat.

Then he smiles his great big maniacal grin just as our pursuers burst out of the trees, their horses’ hooves churning up the forest floor.

Yannic makes the first move, launching one of his rocks with his customary skill and striking one of the foremost men on the temple. I raise the crossbow and take the leader between the eyes. While he is still reeling from the force of the bolt, I drop the bow and reach for my throwing knives. Beast keeps the rock wall at his back and stands in his stirrups to swing at th

e four horsemen who engulf him.

Even as my first three knives hit their targets, I know there are too many. I reach for the sword strapped to my saddle, but before I can free it, one of the men charges me. I throw myself to the left as he swings, and misses. Before he can swing again, there is a loud thwap, and he slumps forward on his horse. I send a silent Thank you to Yannic, until I see the arrow in the man’s back. Yannic does not have a bow.

I have no time to look for the archer as I struggle to free my sword from its scabbard. A half a dozen men have Beast pinned against one of the stones. His sword arm flashes quick and bright, but his left arm is barely able to move the ax. I spur my horse toward him, lunging forward with the sword. It is an awkward, clumsy thrust but it does its job.

Except that the soldier’s horse jerks away, taking the dying man and my sword with it. Merde. I pull my last two daggers from my wrists. I glance at Beast. Should I save them for us or use them to attack? Before I can decide, arrows rain down from the trees, shocking me into stillness. Even as I ready myself for their sharp bite, five of d’Albret’s men wheel around to meet this new attack, and a second volley is let loose. Suddenly, the small clearing is alive with movement as the trees and the forest floor itself comes to life, spitting out creatures of the old legends. Or demons spawned in hell. They are dark of skin and misshapen. One has a leather nose, another’s arm seems to be made of wood, and a third appears to have had half his face melted away. Whatever their infirmities, they finish off the rest of d’Albret’s men with ruthless efficiency, pulling the men from their horses and dispatching them with wicked little blades or quick twists of their necks. Within the span of a dozen heartbeats, all of d’Albret’s soldiers are dead, and we are surrounded.

Chapter Twenty-Two

BEAST RAISES HIS DROOPING SWORD, but a curt command from the man with the leather nose stays his hand. He tilts his head up to the branches above us. I follow his gaze and see a dozen archers hidden there, arrows trained upon us. We all eye one another warily.

The leather-nosed man steps forward. He is small and wiry and wears a dark tunic and a leather jerkin over patched breeches. As he moves out of the shadows, I see that he is not as dark-skinned as I had first thought—he is coated with grime. No, not grime. Dust. Or ash, mayhap. As he draws closer still, I see a single acorn hanging from a leather cord around his neck, and then I know. These are the mysterious charbonnerie, the charcoal-burners who live deep in the forests and are rumored to serve the Dark Mother.

With no more noise than a breeze rustling through the leaves, the rest of the charbonnerie emerge from their hiding places. There are twenty of them, counting the archers in the trees. I glance over at Beast. We cannot fight our way out of this one.

With an effort, Beast straightens in his saddle. “We mean you no harm. By right of Saint Cissonius and the grace of Dea Matrona, we wish only to pass the night in the forest.” It is a bold gambit, and a smart one, for while the Dark Matrona is not accepted by the Church, the Nine are her brethren gods, and invoking their blessing cannot hurt.

One of them, a thin fellow with a chin and nose as sharp as blades, spits into the leaves. “Why do you not spend the night at an inn, like most city dwellers?”

“Because there are those who wish us ill, as you just saw.” As Beast speaks, another of the charcoal-burners—a young, gangly fellow who is all elbows and knees—sidles up next to the leader and whispers something in his ear. The leader nods, his gaze sharpening. “Who are you?”

“I am Benebic of Waroch.”

The man who had murmured in the leader’s ear nods in satisfaction, and whispers of the Beast go up around the charcoal-burners. Beast’s exploits have made him famous even among the outcasts.

“And who is it the mighty Beast wishes to avoid?”

“The French,” Beast says. “And those who would support them. At least until I can heal and meet them in a fair fight.”

I hold my breath. The charcoal-burners hate the French as much as most Bretons do, and I can only hope that having a common enemy will give us common cause. One of the older men, the one with a wooden arm, nudges a body with his foot. “These men aren’t French.”

“No, they’re not. But they are traitors to the duchess and wished to detain us.” Then Beast grins one of his savaage grins. “There is plenty of room for you in the war against the French, if you so desire. I would be honored to have such skilled fighters on my side.”

There is a long pause, which makes me think the charbonnerie receive few such invitations.

“What is in it for us?” the sharp-faced man asks, but the leader motions for him to be silent.

Beast smiles. “The pleasure of beating the French.” To him, any fight is its own excuse.

The leader reaches up and scratches his leather nose, suggesting it is a recent replacement. “You can spend the night in the forest, but under our watch. Come. Follow us.” He motions to the others, and a half a dozen of them fall in around us.

They are eerily silent as they guide us deeper into the forest, and our horses’ hooves are muffled by the thick layer of decaying leaves on the ground. The gangly youth cannot keep his eyes off me, and when I catch him staring, he blushes to the roots of his hair.

The trees here are ancient, tall and thick and gnarled like old men bent with age. Even though there are hours of daylight left, little sun gets through the thick tangle of foliage overhead.

At last we reach a large clearing ringed by a half a dozen mounds of earth, each one as big as a small house. Smoke burbles from holes in the mounds, which are tended by nearby men. Interspersed among the mounds are small tents made of stripped branches and stretched hides. Cooking fires are watched over by drably dressed women, while dark, gritty children play close by. When we enter the clearing, everyone stops what they are doing and turns to look at us. The youngest child—a girl—sidles up to her mother and slips her fingers into her mouth.

The leader—Erwan is his name—grunts and points to a section of the clearing far away from the earthen mounds. “Make your camp there.”

All of them watch as Yannic and I dismount, secure our horses, then turn to help Beast off of his.

His breath comes in quick, shallow gasps. “Did you take a new injury?” I ask quietly.

“No.” His grunt is followed by a short bellow of pain. By the time we have him off his horse, the entire camp knows of his condition. Yannic and I are able to steer him but a few feet before he comes to a complete stop. “I think this is a good place to make camp,” he says, then grabs for a nearby tree so he will not crash to the ground.

“Not sure that one is going to live through the night,” the wooden-armed man mumbles, and I glare at him.

The gangly fellow catches my eyes. “Oh, don’t mind Graelon, miss. That’s just his way.” He glances mischievously at the old man, then leans in closer to me. “He was like that before the fire got his arm.” The youth’s charm is infectious.

“I’m Winnog, my lady. At your service.”

“As if she’d have you,” someone mutters.

Ignoring the mutterer, I give Winnog my brightest smile. “Thank you.” As I turn back to Beast’s side, it is all I can do not to clap my hands at the onlookers and cry, Shoo! But they would no doubt consider that a rude repayment of their hospitality, meager as it is.

I sense a movement behind me and feel the beating of a lone heart. Still untrusting of these charbonnerie, I whirl around, hand going to the knife concealed in my crucifix.

The woman I see pauses and casts her eyes down in a gesture of submission. She is dressed in a dark gown, and, like the rest of the women, her hair is wrapped tightly in a coif of some kind. She carries a small sack. “For his wound,” she says. “It will help.”

After a moment, I take the sack from her and peer inside. “What is it?” I ask.

“Ground oak bark to keep infection from setting in. And ashes of burned snakeskin to hasten the healing.”

“What is y

our name?” I ask.

She glances up at me, then down again. “Malina.”

“Thank you,” I say, and mean it. For I am running out of ideas on how to keep Beast’s wounds from overtaking him before we make it to Rennes.

“Do you need help?” she asks shyly.

While I am certain Beast will hate having his weakness seen by others, it seems prudent to accept any help they offer, an attempt to forge some tenuous bond between us. “Yes, thank you. Do you have any hot water?” She nods, then slips away to fetch it. While she is gone, I quickly sniff the oak bark and the ashes, then put a dab to my tongue to be certain it will do no harm.

“It was not in jest that I invited them to fight with us.” Beast’s voice rumbles up at me. “Did you see how ferocious they were? How unexpected their tactics?” He is as excited as a squire with his first sword. “They could prove valuable allies.”

“If they do not stab us in the back,” I mutter. “Are they not known to be clannish and untrustworthy?”

Beast considers a moment. “Clannish, yes, but that is not the same as being unworthy of trust.”

Malina returns just then, bringing a halt to our conversation. She and I tend Beast’s wounds while he lies back and pretends he is dozing, but his jaw clenches as we work on him. By the time we are done, supper is ready, and, much to my surprise, we are invited to partake of it. It seems we are to be treated as guests rather than prisoners, then. Wishing to capitalize on this, I take one of the cheeses and the two roast chickens that Bette gave us to contribute to the meal.

The charbonneries’ eyes widen with pleasure and the unexpected bounty, and when I sit down to eat, I can see why. Dinner is some sort of mash—acorn, I think. As I take a bite, I cannot help but remember how I called the convent’s food pig slop and how Sister Thomine threatened to force it down my gullet.

A lump forms in my throat, one that has nothing to do with the mash and everything to do with a sense of deep homesickness, for as much as I rebelled against the convent, it was the safest place I have ever lived. I miss Ismae and Annith more than I ever thought possible.

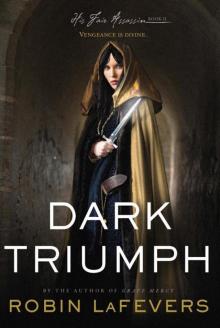

Dark Triumph

Dark Triumph Grave Mercy

Grave Mercy Courting Darkness

Courting Darkness Igniting Darkness

Igniting Darkness Grave Mercy (Book I) (His Fair Assassin Trilogy)

Grave Mercy (Book I) (His Fair Assassin Trilogy) Mortal Heart

Mortal Heart Grave Mercy (Book I): His Fair Assassin, Book I (His Fair Assassin Trilogy)

Grave Mercy (Book I): His Fair Assassin, Book I (His Fair Assassin Trilogy) Dark Triumph (His Fair Assassin #2)

Dark Triumph (His Fair Assassin #2)